“Fixed” Memory Pool Design

This post describes a memory allocation strategy I call a “fixed” size memory pool.

Recently I decided to re-write my virtual machine Drey almost completely in the C programming language, using no external libraries except for the networking via ZeroMQ. This is mostly for fun, to see if I can remember how to program in C again and write a load of low-level stuff (apologies if my C is currently terrible!.)

Drey executes programs written in a much higher level language (typically Scurry), its purpose being to remove all low level details and provide an experience for the author focused on game logic only. As such, the virtual machine implementation must manage the memory itself, not knowing how much of what size memory it will need up front.

Since the system calls malloc/free are relatively slow and will fragment the heap, especially for lots of small object allocations, a memory management system will be required.

(actually, I could probably get away with using malloc since performance doesn’t really matter in Drey, but where’s the fun in that!)

Requirements

At the very core of the new memory management system are (currently) two allocators that are the building blocks for other data structures.

- fixed/static sized memory pool

- dynamic sized memory pool

In both cases the terminology of static/fixed/dynamic is a little unclear; Usually “fixed” or “static” means the size of the pool can never change. A requirement of both pools is that they are able to resize themselves at runtime - since I have no idea what program the VM might be running - but I was at a loss of what else to call them.

The usage of realloc() to resize OS allocated memory means the addresses of the pools might change, thus they will have to be relocatable in some manner.

The dynamic pool is able to allocate, free, extend and reallocate/resize arbitarily sized chunks of memory, whilst the fixed is tied to a size and simply allocates and frees blocks.

This post concentrates on the fixed size pool, which must meet the following requirements

- Deals only in fixed sized blocks of memory

- Can be dynamically resized via realloc() without breaking everything

- Must be extremely fast at allocating and freeing blocks (cos why not)

- Must use no additional storage to track free blocks of data (otherwise - how do you manage THAT memory!)

Overall Design

The fixed sized pool is initialized by allocating a chunk of memory via malloc(), the very start of which contains a few bytes of control data (we will see this shortly).

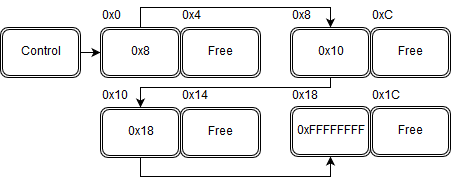

The memory pool uses a relative positioning system that ensures relocatability. Upon initialization, a free list is setup within the unallocated memory, where each free block holds the offset from the base address to the next free block. As an example, here is a pool initialized with a block size of 8 bytes, initially with 4 unallocated blocks in it. This is a 32bit progam, thus the memory addresses are 32 bits (4 bytes) each.

Note that the requirement of the offset to be 4 bytes means the minumim block size for this pool is also 4 bytes.

You can see here the first block has an offset of 0x8, the second 0x10 and so forth, with the last block having the special value of –1 to indicate the end of the list. You will notice this is an absolute offset rather than the “index” into the memory array via the block number. When accessing an element, we need only add the offset to the base address of the data, without having to also multiply it by the element size.

The control data contains information on the block size, element count, the owner of the pool (more on this later) and the offset of the first free block.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

typedef struct MemoryPool_Fixed

{

struct MemoryPool_Fixed** owner;

int free_offset;

int element_size;

int element_count;

void* data;

} MemoryPool_Fixed;

|

Allocation

Allocating a block is fairly simple. The control data contains the offset of the first free block. The algorithm jumps to it, replaces the first free block offset with the one it finds at that location, and returns the offset of the block to the caller. (ignoring the case where there’s no free block for now.)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

int fixed_pool_alloc(MemoryPool_Fixed* pool)

{

int offset = pool->free_offset;

int* element = (int*)((int)&pool->data + offset);

pool->free_offset = *element;

return offset;

}

|

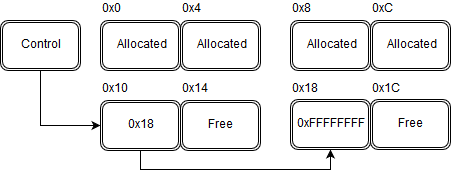

It doesn’t get much faster than that! Here’s what it looks like after the first two blocks have been allocated

Notice that when the last block is allocated, the first free block will point at 0xFFFFFFFF (–1), the special value indicating we’re out of blocks.

Freeing

Freeing a block is equally simple. Since we know the blocks are all the same size, our pool is never subject to any kind of fragmentation, and it does not matter what order the blocks are allocated. There is either a block available, or there isn’t. For this reason, no matter where the block to be released is, we can simply replace it as the new first free offset, and insert into its place whatever the first free offset was.

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

void fixed_pool_free(MemoryPool_Fixed* pool, int offset)

{

int* element = (int*)((int)&pool->data + offset);

*element = pool->free_offset;

pool->free_offset = offset;

}

|

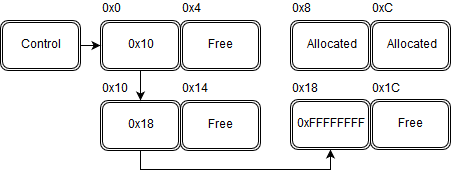

Again, this is blazingly fast with a minimum of overhead. After freeing the first block of memory, it now looks like

Accessing

Given the memory location and an offset, obtaining a pointer to the actual data should be fairly obvious;

1 2 3 4 5 |

void* fixed_pool_get(MemoryPool_Fixed* pool, int offset)

{

int* address = (int*)((int)&pool->data + offset);

return (void*)address;

}

|

This level of indirection slows it down a tiny fraction (this function will of course also be inlined), not to mention being a bit cumbersome to actually use directly, but it gurantees you will get the correct block of data, even if the memory pool had to move in its entirety. The only thing you must be sure of is where the base of the pool is. You will need to be careful with the returned pointer, it is possible that whilst holding it, if you allocate something else to this pool that causes it to be relocated, your old pointer is going to be wrong. More on how to manage this in another post.

Relocation

When the pool is first initialized, you must pass it a pointer to a pointer that will hold the base address of the pool. If the pool has to be moved for some reason, it simply updates your pointer to its new location, and the rest of your program goes merrily on its way accessing its allocated memory via offsets, not knowing any difference.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

void fixed_pool_init(MemoryPool_Fixed** owner, int element_size, int initial_element_count)

{

int actualElementSize = (element_size * initial_element_count);

int actualSize = actualElementSize + sizeof(MemoryPool_Fixed);

MemoryPool_Fixed* data = (MemoryPool_Fixed*)malloc(actualSize);

data->free_offset = 0;

data->element_size = element_size;

data->element_count = initial_element_count;

data->owner = owner;

int address = (int)&data->data;

int offset = 0;

//setup free list

for(int i = 0; i < initial_element_count - 1; i++)

{

offset += element_size;

*(int*)address = offset;

address += element_size;

}

*(int*)address = -1;

//assign owner to the new address

*owner = data;

}

|

This does impose the restriction that only one pointer can know about the location of the memory pool - this is fine, and as a fundamental low level building block, we would not want to be sharing these pointers around anyway, as all memory allocation will come indirectly from a memory manager and / or higher level data structures.

Let’s see how the resizing algorithm works. Essentially, it attempts to double its size via an OS call to realloc(). The nature of realloc() will cause it to extend the existing memory blck if it can, and if it can’t it will copy the entire block to a new location, free the old one and return a pointer to the new location. All that’s left for us to do then is setup the new memory with the offset free list, and update the owner’s pointer to the new location. This all happens in the alloc() call if the offset value is –1, the special value indicating the end of the list.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 |

int fixed_pool_alloc(MemoryPool_Fixed* pool)

{

int offset = pool->free_offset;

if(offset == -1)

{

int oldCount = pool->element_count;

int newCount = oldCount * 2;

int newElementSize = (newCount * pool->element_size);

int newSize = newElementSize + sizeof(MemoryPool_Fixed);

printf("out of memory, reallocating as size %i\n", newSize);

pool = (MemoryPool_Fixed*)realloc((void*)pool,newSize);

pool->element_count = newCount;

offset = pool->free_offset = (oldCount + 1) * pool->element_size;

int address = (int)&pool->data + offset;

//setup linked list in the new block

for(int i = oldCount; i < newCount - 1; i++)

{

offset += pool->element_size;

*(int*)address = offset;

address += pool->element_size;

}

*(int*)address = -1;

offset = pool->free_offset;

//rewrite owner's reference address

*pool->owner = pool;

}

int* element = (int*)((int)&pool->data + offset);

pool->free_offset = *element;

return offset;

}

|

Conclusion

That’s it - an extremely fast fixed size memory pool, with hardly any additional memory overhead, that resizes itself automatically and provides re-locatable memory via a relative offset system.

The pool is not completely robust - I am not checking to see if malloc/realloc fail, for example. It is also not at all thread safe, but these are not concerns for the system I am building. I am also not aligning the data in any way - I don’t think I will need to, it can be accommodated if required, though.

Note that the decision to setup the free list in advance pays a price upon initialization and resizing. This can be mitigated by remembering the total amount of allocated blocks, and building the list as you go during allocations, which is slightly slower when allocating but effective for very large sized blocks of data. For my use I decided on pre-building the list, but both approaches are interesting to try out.

This scheme is typically 30x+ faster than using malloc (not when resizing, obviously) and not subject to any memory fragmentation at all. I do not, however, include any mechanism with which to shrink or compact a block of mostly unused data.

Next time we will see how the more complex dynamic memory pool is implemented.